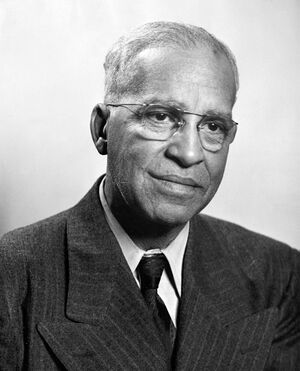

‘Cap” Wigington and the Towering Achievements of America’s first Black Municipal Architect.

Clarence Wigington’s early years and training.

The 1910 census records only 59 black architects, artists, and draftsmen in the United States. Clarence Wesley Wigington was born in 1883 into this culture of segregation, oppression, and limits for African Americans. He never got formal training or a degree, or a certification in architecture, but his skills and determination would lead him to become America’s first black Municipal Architect. He left behind a legacy of excellence embodied in his work in St. Paul, Minnesota. Many of these structures still stand and are a part of everyday life in the city. One of the best known is the Highland Park Water Tower.

Wigington was born in Lawrence, Kansas to a mixed-race father and his schoolteacher wife. The family of 12 children moved frequently in Wigington’s early years before finally settling down in Omaha, Nebraska. Wigington’s artistic skills were obvious early on and at the age of 15 he won the award for best drawing at the Trans-Mississippi World Fair. His skills drew the attention of two of his elementary school teachers who encouraged him to go to art school and offered to cover half of the tuition.

Rather than attending art school Wigington set out to find a job after graduation and secured a position in the office of Thomas R. Kimball, a well-respected architect. The structural engineers and chief draftsman from the office tutored young Wigington and in 1908 he left the position to open his own office. He also met and married Viola Lessie Williams. Wigington was hired by both white and black clients and obtained commissions for several dwellings as well as a factory. In 1914 the Wigingtons joined other African Americans in the Great Migration and moved north to St. Paul.

Wigington launches his legacy in the city of St. Paul.

St. Paul had been growing rapidly and was leaving its infrastructure behind. At the same time residents wanted a city that reflected their prosperity and status as the capital of the state of Minnesota. The city government had just been restructured in response to extensive corruption, and this included the new Office of City Architect. This new form of government was under a commission and included service exams to measure a candidate’s merit, rather than their influence and connections.

It was Viola who saw a posting for the position of architectural draftsman and encouraged Wigington to take the exam. He passed with the highest score and in November of 1915 accepted the position of Senior Architectural Draftsman, thus becoming the nation’s first black municipal architect.

Wigington would work on over 90 buildings in St. Paul ranging from fire stations to airports to fanciful ice castles for the winter carnival. His work spans a time when there were great changes in how America approached municipal architecture. St. Paul’s expansion was guided by influences such as the City Beautiful movement and new ways of designing parks and schools. Wigington left an impact in many areas of the city’s growth, but park buildings were his forte and some of the schools he build are still active today. He would stay with St. Paul until retirement in 1949 with only a few periodic breaks from his time in the city.

The 16th Battalion of the Minnesota Home Guard: Finding a way for black patriots to serve their county in a time of segregation.

Wigington quickly built a reputation as a leader in St. Paul’s black community and when the U.S. entered World War I on April 6, 1917, he joined other patriotic African Americans in looking for a way they could play a role in the fight. At first the US government refused to induct African Americans in the armed services. Even white liberals were nervous about an insurrection if politically disenfranchised people were given arms and military training Eventually, the US established African American units primarily led by white officers.

Early in the war National Guard units were called into federal service and the Minnesota Home Guard was organized to protect the home front. Wigington petitioned the governor, J. A. A. Burnquist. to form a separate battalion of the Home Guard for black Americans. Burnquist was the president of the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP and had been looking for an opportunity to take a leadership role in combating racism. He knew that proposing an integrating armed services would be political suicide and Wigington’s proposal was a win-win for both men. The result was the 16th battalion, the first Minnesota-recruited African American miliary unit in state history.

Around 500 men enlisted in the 16th battalion and successfully demanded that their officers be men of color. The black community embraced the battalion and held rallies and fundraisers to support the men. The 16th battalion band became especially popular. Newspapers from the time show announcements of events proudly boasting that the band will be performing. In April of 1918 Wigington gave a speech to a group of men before they were sworn in and he became the captain of Company A. For the rest of his life he would be known by the nickname, “Cap”. On Memorial Day the 16th marched in parades alongside all white Home Guard units. Newspapers remarked that the 16th got special applause.

The Highland Park Water Tower and the architecture of a neighborhood symbol.

With the end of the war members of the Home Guard mustered out and Wigington continued his career in architecture. Three of the buildings he designed have been added to the National Registry of Historic Places. Another structure, the Highland Park Water Tower, was designated an American Water Landmark by the American Water Works Association.

Elevated water storage tanks became important components of municipal water systems in the late 19th century as communities grew larger and more dependent on water distribution systems. The elevated reservoirs maintain constant pressure and insure storage for fighting fires. They are also conspicuous and symbolic structures, usually visible from a long distance. The Highland Park Water Tower sits on the second highest elevation in the city of St. Paul and is a familiar landmark and symbol of the local neighborhood.

The Mediterranean Revival style water tower was completed in 1928 and stands 127 feet tall with a 200,000 -gallon tank constructed of riveted steel plates. The cost of the build was $69,483, the equivalent of over $1,300,000 in 2025.

There are three sections to the tower. The base is 40 feet wide and consists of smoothly dressed, random ashlar Kasota stone. The middle section is built of tan, pressed brick with several windows. The top observation deck is coursed ashlar Bedford stone. The water tower sits at the edge of a large expanse of parkland and from a distance the colors of the different materials blend together into a warm, inviting tan. Like so many of Wigington’s buildings, the closer you get the clearer his attention to detail becomes obvious down to the solid wooden doors braced with ornate metalwork.

The Highland Park Water Tower is no longer in service and has been replaced by underground reservoirs and modern tanks nearby. The tower is open to the public twice a year and people stand in long lines waiting to climb the 151-step circular staircase to the observation desk. Like me, many people come year after year to make the climb. They take selfies by the windows, reminisce about growing up in the neighborhood, or just stand quietly with their thoughts as they take in the view from the top of the tower that Cap built.